When students begin to learn Mandarin online or study with an online Chinese teacher, they often focus on pronunciation, tones, and vocabulary. Yet the written form of the language carries an equally profound cultural significance. Chinese calligraphy, more than a practical writing system, represents an artistic tradition that reflects the history, philosophy, and aesthetics of China. Its evolution over more than three millennia demonstrates both the continuity and the adaptability of Chinese culture.

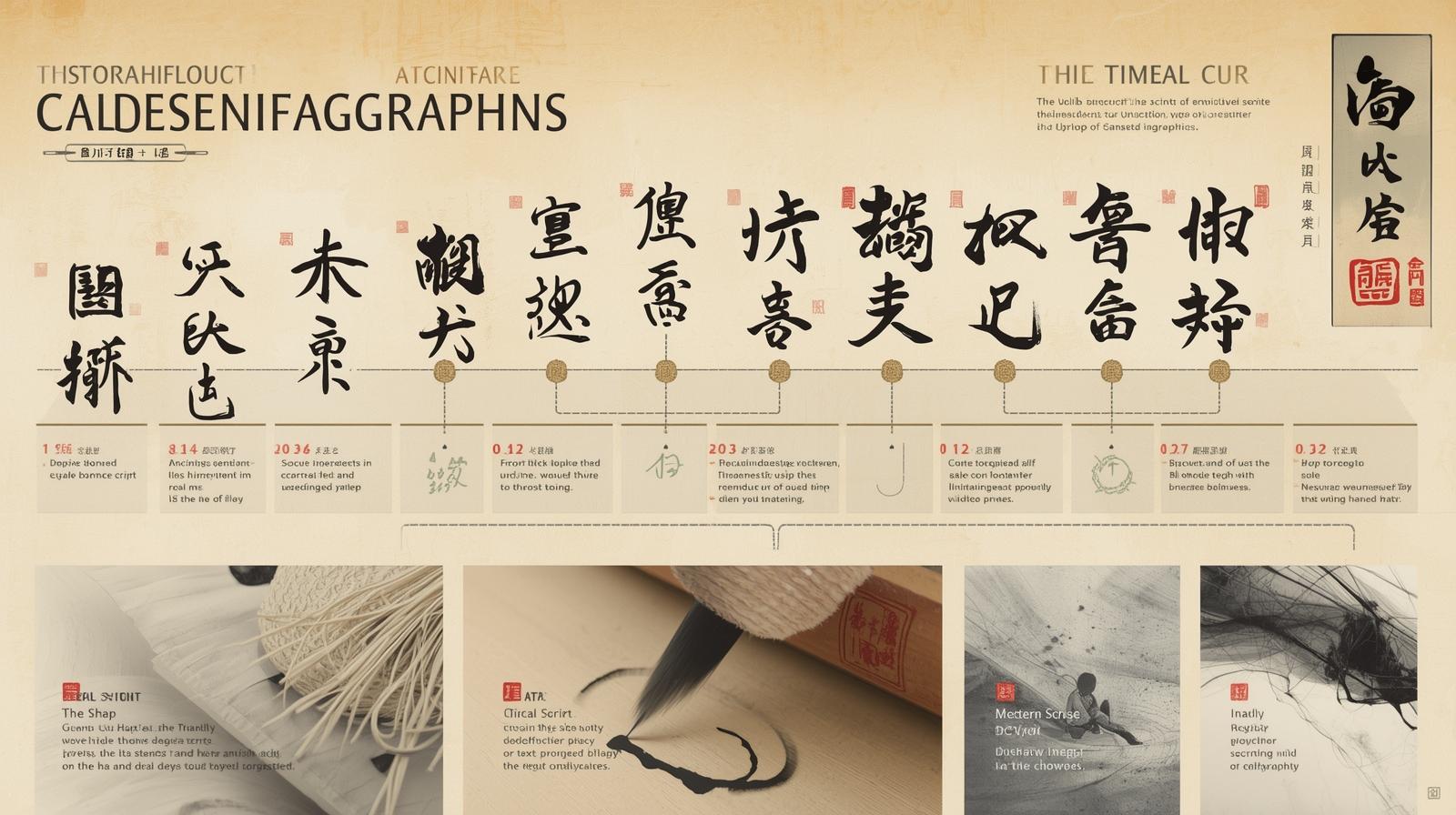

Examples of Chinese Script

The earliest known examples of Chinese script are found on oracle bones from the late Shang dynasty (c. 1200 BCE). These inscriptions, known as jiaguwen (甲骨文), served ritual and divinatory purposes and stand at the beginning of a continuous written tradition. In the Zhou dynasty, inscriptions on bronze vessels (jinwen 金文) displayed greater regularity and often carried commemorative functions.

Qin dynasty (221–206 BCE)

A major transformation took place during the Qin dynasty (221–206 BCE), when the small seal script (xiaozhuan 小篆) was standardized as part of the unification policies of the first emperor. This reform marked the beginning of a conscious effort to systematize writing on a national scale.

Clerical Script

The Han dynasty introduced the clerical script (lishu 隶书), a more practical and rectilinear form suited for administration. This script laid the groundwork for the regular script (kaishu 楷书), perfected by calligraphers in the following centuries. Masters such as Wang Xizhi (王羲之), Wang Xianzhi (王献之), and later Yan Zhenqing (颜真卿) transformed writing into a medium of artistic and moral expression. Alongside regular script, running script (xingshu 行书) and cursive script (caoshu 草书) emerged, valued for their rhythm, spontaneity, and expressive power.

Calligraphy reached its cultural height during the Tang and Song dynasties, when it became an essential aspect of education and civil service. Skill in calligraphy was regarded as evidence of intellectual cultivation, self-discipline, and character. The act of writing was not limited to transmitting information but also to embodying one’s inner disposition, harmonizing movement, ink, and paper.

In the modern era, calligraphy has shifted from a practical necessity to a cultural and artistic practice. Although printing and digital writing systems dominate daily life, calligraphy continues to be taught in schools, practiced by artists, and displayed in exhibitions. It symbolizes continuity with the past and remains a respected form of personal and artistic cultivation.

Final Words

Learning Chinese today, calligraphy provides more than historical insight. It helps illuminate the structural principles of characters, deepens appreciation for the visual dimension of the script, and connects language study to broader traditions.

This is why institutions such as GoEast Mandarin in Shanghai incorporate calligraphy into their cultural courses. By linking linguistic training with artistic practice, they demonstrate how mastering a language can also mean engaging with the cultural values that shaped it.